The beatings will continue until morale improves

As growth slows around the world, the Federal Reserve begins tightening financial conditions

Economic Developments

Carefully Fall Into the Cliff (Part Deux):

In our last issue (Carefully Fall Into the Cliff - January 29, 2022), we noted that as inflation accelerated, the Federal Reserve increased its posturing toward battling inflation at the expense of global markets. Specifically, we noted that:

As financial conditions transitioned between paradigms (from a deflationary decreasing interest rate environment to an inflationary increasing rate environment), volatility typically erupts as market participants struggle to understand their new environment. We further noted that during such a period significant price swings can occur.

Credit conditions, particularly abroad, could deteriorate (whether caused actively by the Federal Reserve via tightening financial conditions or stalling growth) and that the Federal Reserve would likely ignore such deterioration in favor of focusing on its “price stability” mandate.

As mortgages rates begin to rise, housing demand could be significantly impacted. Similarly, as corporate rates rise bond markets could begin to be affected.

Because the US dollar is the reserve currency of the world and most debt (i.e. foreign debt) is denominated in US dollars, Federal Reserve tightening financial conditions domestically, tightens financial conditions abroad. We also noted that this may result in tightening of financial conditions in countries whose economies are in need of looser financial conditions.

As the months have progressed, we have seen these 4 observations unfold in real-time.

First, since our last edition on January 29th, the S&P index has experienced four >300 point swings (from roughly 4,331 to 4,590 to 4,144 to 4575 and now back to 4200) with 1-month realized volatility the highest in March year-over-year (SP Global S&P500 1-month realized volatility). In spite of this volatility, the S&P remains only ~10% off of its peak.

It should also be noted that reflected in this market volatility are 4 divergent narratives:

(1) Bullish: The Federal Reserve will reverse course, slow the pace of tightening or begin loosening policy and risk assets will rise on the additional stimulus (or lack of tightening). Among this group there is a subset who believe inflation will rise rampantly as a result, while there is another who believes inflation is transitory and will abate as growth slows (although for this group the stimulative effect of an easing Fed will outweigh the effects of slowing growth).

(2) Mildly Bullish: The Federal Reserve will engineer a “soft-landing” by carefully modulating tightening to match economic data. This view is the U.S. government’s view via the U.S. Treasury Secretary (Yellen sees 'soft landing' for US economy as Fed raises rates).

(3) Mildly Bearish: The Federal Reserve will tighten until reaching a terminal rate of ~3.25% as articulated in the Federal Reserve’s “dot plot” of the Effective Federal Funds Rate (Federal Reserve - Summary of Economic Projections - March 16, 2022) or roughly 7-9 hikes this year in 50bps increments (every meeting being considered a “live” meeting). The Federal Reserve will also begin running off its balance sheet at roughly double the pace it attempted in 2018 (which blew up the repo markets at that time, but is perceived as non-threatening to the now Federally-fortified repo market) or approximately $1.2 trillion per year of run-off (around $100 bn per month in a mix of treasuries and agency-MBS). In this scenario, the economy (and financial system) is viewed as strong enough to “take it” and “price stability” (aka inflation) will be brought back into control via restrictive policy (however restrictive as necessary to get inflation back down to a ~2% long-term target in the Federal Reserve’s discretion). (Fed begins inflation fight with key rate hike, more to come).

(4) Bearish: The Federal Reserve will continue tightening/hiking until something in the credit markets “break”; either the housing market (via a mortgage market flooded with agency-MBS), corporate credit (as spreads widen) or repo (as banks either lose the ability or willingness to intermediate collateral trades).

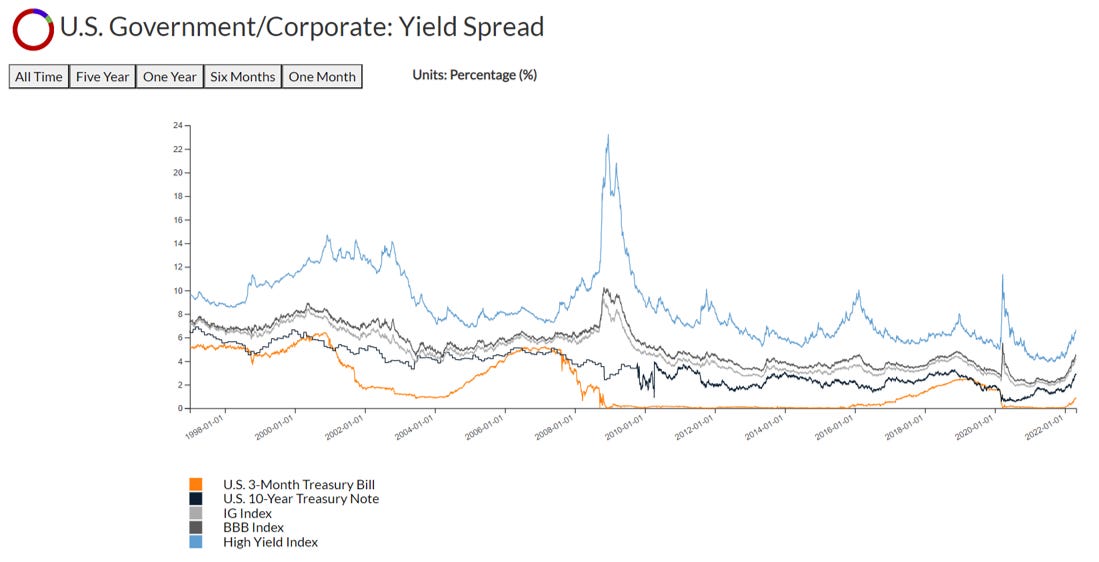

Second, corporate credit conditions have begun to deteriorate (particularly abroad). As support for credit markets has been withdrawn (on March 9, 2022, the Fed officially conducted its final open market purchase effectively ending its QE program), interest rates have increased at one of the fastest paces on record. As a result, prices in US corporate credit markets have declined significantly. Spreads remained tight initially, while rate risk eroded bond value, until this rate risk began to affect refinancing (debt now needing to “roll” or be refinanced at a higher cost). As a result spreads have begun to widen (roughly ~150bps in Investment Grade and roughly ~400bps in High Yield). Bond issuance also slowed somewhat as investors awaited market reaction to a tightening Fed. Debt issuance in Asia-Pacific also fell notably as China’s property sector continues to be battered by delinquencies.

Third, mortgage rates have risen substantially since the end of the Fed’s open market operations. The average price of a 30-year fixed rate mortgage was approximately 3.76% on March 3rd, a few weeks later it now costs 5.29% on April 28th. This will likely contribute to a softening in sales of existing homes which began in February (down roughly 7% from January). Notably mortgage lenders have begun laying off large percentages of staff due to declining demand for refinancing and originations (Wells Fargo Confirms Mortgage Staff Layoffs).

Fourth, as the Federal Reserve has begun tightening, growth has begun to sputter around the world. Most notably, China remains plagued by a slowing housing market and the Eurozone is now plagued by a ground war occurring between the Russian Federation and the Ukraine. Notably Asia-Pacific economies (particularly China and Japan) have begun easing policies in an effort to soften the blow to growth. The ECB has accelerated its end to Quantitative Easing to July (paving the way for rate hikes ostensibly in an effort to keep pace with the U.S.), while its economy continues to drift into recession amidst an energy crisis. Meanwhile, the anglosphere (the U.S., the U.K., Canada and Australia) have remained committed (as of now at least) to tightening financial conditions. Because capital flows out of these developed nations (most notably out of the U.S. as the reserve currency) to Asia-Pacific, emerging markets and the Eurozone; tightening financial conditions in these developed nations is likely to cause a capital flight out of nations already suffering from growth slow-downs. This is most dramatic in Japan, where the Bank of Japan has begun attempting to defend bond yields through yield curve control at the expense of its currency, and China, where the Yuan is faltering amidst attempts by the CCP to loosen credit in an effort to prop up an insolvent real estate market (the primary driver of China’s domestic economy).

The Beatings Will Continue Until Morale Improves:

To be sure, each of the diverging narratives noted above contain an important element of truth, but for the sake of analysis, we’ll begin with the view of the Fed Chair, because the market conditions are dominated by monetary policy and the Federal Reserve controls monetary policy.

From Powell’s statements at the March 16th FOMC meeting we can deduce a few key points:

(1) Powell believes inflation is too high and needs to be brought under control.

“We're acutely aware of the need to restore price stability while keeping a strong labor market….We're not going to let high inflation become entrenched. The costs of that would be too high….So, frankly, the need is one of getting back up, getting rates back up to more neutral levels as quickly as we practicably can...” (Transcript of Chair Powell's Press Conference - March 16, 2022)

(2) Powell believes the economy is strong (and therefore no longer in need of support). For this determination of “strength”, he is primarily looking at the labor market.

“Well, if you take a look -- take a look at today's labor market, what you have is 1.7 plus job openings for every unemployed person. So that's a very, very tight labor market, tight to an unhealthy level, I would say.” (Transcript of Chair Powell's Press Conference - March 16, 2022)

(3) Powell wants to “bring down” demand such that it is balanced with supply. Presumably this means “destroy” demand to reduce inflation and is an implicit recognition that inflation is not merely a supply chain issue, but was caused in part by fiscal stimulus.

…the idea is we're trying to better align demand and supply, let's just say in the labor market…And basically across the economy, we'd like to slow demand so that it's better aligned with supply…And that over time should bring inflation down…we have to restore price stability.” (Transcript of Chair Powell's Press Conference - March 16, 2022)

(4) Powell intends to use interest rate increases and balance sheet run-off to tighten monetary policy and slow economic activity in an effort to realign supply and demand. This is viewed as an acceptable risk because the American economy is “strong” and can “handle” it.

“And I just would want people to understand that…the way we do that is by raising interest rates and by shrinking our balance sheet. And so financial conditions will become, at the margin, less supportive of various kinds of economic activity. That will slow the economy…And that means the economy, we think, can handle interest rate increases.” (Transcript of Chair Powell's Press Conference - March 16, 2022)

As we noted in our previous issue, the easiest way for the Fed to regain control of inflation is the destruction of credit and recession. This destroys demand (as the Fed Chair notes) which brings down inflationary pressures (although pressures caused by true supply chain bottlenecks will persist until capacity is increased).

Or said another way, the Federal Reserve intends to hurt the economy and continue striking it until inflation begins behaving itself again and the pain of inflation ceases. The interest rate beatings will continue until the inflation morale improves.

From this position, the four divergent market positions (mentioned above) emerge:

(1) Bullish: Some market participants believe the Fed simply won’t do it. The economy is too weak and the Fed will reverse course to support it. This is, in part, rooted in some anchoring bias in which market participants have grown accustomed to ever increasing amounts of monetary and fiscal support at the first sign of market distress.

As we noted in prior issues, we believe this view is incorrect, because it fails to account for the fact the Federal Reserve’s prior support was rooted in a desire to save “funding markets” and not risk assets. (For more information on this please feel free to revisit our earlier edition: Structural Changes in Treasury Markets Reveal Policy Shift - September 1, 2021). Despite this misunderstanding, there is still some truth embedded in this statement. While funding markets have been reinforced by the Federal Reserve, credit markets are far more fragile than they have ever been and only a few rate hikes is likely to cause distress across certain credit markets (to be sure it is already causing distress abroad). It remains an open question how much pain the Federal Reserve is willing to allow markets (domestically and globally) to endure. Although as to inflation v. credit markets, as noted above, destroying credit is at least in part, the intention and likely to be permitted at least to some degree.

(2) Mildly-Bullish: Some market participants believe that the Fed will be able to engineer a “soft-landing”; most notably Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen. In such scenario, the Fed causes just enough demand destruction to bring demand back in line with supply. This would require pushing the employment rate up slightly (to remove the “tightness” in the labor market), while not significantly impacting economic growth. It’s a goldilocks scenario that requires precise adjustments to get tightening policy just right.

This scenario seems extremely unlikely. As Former Federal Reserve Governor Bill Dudley noted in public remarks, a “soft-landing” (in the history of the Federal Reserve) has never been achieved in a situation where creating “economic slack” required demand destruction sufficient to push up the unemployment rate (as it does now). Specifically the former governor cites the Sahm rule (named after economist Claudia Sahm) which states that a recession is unavoidable when the 3-month moving average of the unemployment rate increases by half a percent or more. In order, to prevent a wage-price spiral, the Federal Reserve will very likely need to increase the unemployment rate by at least a half a percent. (Bill Dudley - The Fed Has Made a U.S. Recession Inevitable)

To be sure, there is an element of truth to the “precision” argument, in that the Federal Reserve has prepared the plumbing of the financial system for a tightening cycle. In particular there are robust reserves for banks to avoid collateral shortages and the like, in an environment of tightening liquidity. Similarly, Federal Reserve balance sheet run-off can be modulated through use of treasury bill/note issuance by the U.S. Treasury to soften the blow to the financial system of said run-off (perhaps after a fashion, Yellen’s statement is a statement of belief in her own ability to control the financial systems plumbing). However, historically speaking, monetary policy is subject to “long and variable lags”. Or said another way, monetary policy is a “blunt instrument” not a tool of precision and it seems unlikely this historical episode will prove otherwise (particularly given the distortion in asset prices up the capital structure from Treasuries, which will presumably need to reprice as rates rise on the short and long-end of the curve).

(3) Mildly Bearish: The position of the Federal Reserve Chair largely tracks the position of the U.S. Treasury Secretary (which is sensible they coordinate activity), however, it is notably less rosy. The Fed Chair seems pretty clear that restrictive policy is going to “hurt” the economy. He just seems to believe (or at least he is articulating to the public) that the economy is strong enough to handle it. To make this assurance, the Federal Reserve likens the economic situation to three prior tightening events that did not result in recession or significant market impacts:

• October 1964 to November 1966: The federal funds rates rose from 3.4% to 5.8% in November 1966 (the unemployment rate declined from 5.1% to 3.6%)

• February 1984 to August 1984: The federal funds rate rose from 9.6% to 11.6% (the unemployment rate declined from 7.8% to 7.5%)

• December 1993 to April 1995: The federal funds rate rose from 3% to 6% (the unemployment declined from 6.5% to 5.8%)

These episodes are notably different from the current scenario in three main ways: (1) the current employment rate (3.8%) is much lower than in any of these prior events and the unemployment rate declined in all prior events, (2) the inflation rate is much higher (core PCE running ~5%) than the target inflation rate (2%) and (3) global debt and asset prices are far higher than in prior episodes (due at least in part to ~10 years of price distortions from QE). Given the forgoing, in order to pull the inflation rate down from ~5%, the Federal Reserve will almost certainly need to act with a policy restrictive enough to push up the unemployment rate (in fact at least in part it will be the goal to create slack in the labor force to diminish wage price pressures). Similarly, rates will likely need to rise sufficiently to cause credit destruction in order to bring demand back in line with supply.

(4) Bearish: Given the backdrop, of high corporate debt and a Federal Reserve that owns ~30% of all agency-MBS, it seems likely that the Federal Reserve’s policy of tightening will most assuredly cause repricing. Given, ultra-low rates in the corporate and housing markets (and the relative buttressing of the funding markets/banking system), the capital markets/shadow banking system and housing markets seem most likely to endure distress. (Despite the fact repo markets are buttressed by the Fed, they may experience some distress as well.) Notably, US government sponsored Fannie Mae publicly doubts the probability of a “soft-landing” (Inflation Rate Signals Tighter Monetary Policy and Threatens ‘Soft Landing’).

In many ways, this may in fact be the policy. One of the fastest ways to destroy “demand” is to destroy credit (since credit is a form of money) and it makes some sense to destroy demand in the areas that are experiencing the most extreme “froth” (mainly, corporate credit, equities and housing). The wealth effect works both ways and if you have an overheated economy, one of the easiest ways to destroy demand is to make people feel poorer. Or said another way, the Federal Reserve may very well intend to continuously hike rates (and run-off balance sheet) until it starts to cause this reverse wealth effect. The Federal Reserve “put” has been replaced with a Federal Reserve “call”.

Furthermore, the Federal Reserve efforts to destroy demand will likely need to be more aggressive than market participants are expecting. First, supply side inflation, by its nature, is resistant to monetary policy efforts (it tends to remain sticky until capacity is improved). This may in turn cause the Federal Reserve to inflict increased harm on the demand side of the curve in an effort to restore balance. This is particularly perilous given the debt overhang that lingers over the financial system. Second, the Federal Reserve's forward guidance has left many market participants with the belief the Fed is “all talk no action”. To restore credibility to its messaging, it makes some sense to act aggressively to retake control of the inflation narrative (and then perhaps subsequently ease the pace of action). In essence, the Federal Reserve will beat the market until morale improves.

International (Inflationary) Developments:

It should be noted that while the Federal Reserve is seeking to wrangle inflation geopolitical events around the world continue to exacerbate the supply side of the inflation equation. Most notably in Ukraine and Asia-Pacific.

A Note on Ukraine: Beginning with the invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, energy and food supply chains across Western and Eastern Europe have been significantly disrupted. In particular the flow of natural gas and oil from Russia (caused at least in part by Western sanctions on the Russian banking sector) has been seriously disrupted (more accurately it has created a parallel system of trade with higher input costs among nations cooperating with Russia) and will likely continue to pressure inflation in the form of energy shortages (and price increases). Natural gas and oil are an input product in the production of most commodities around the world (if you want to harvest wheat for instance a diesel powered tractor is likely used in most parts of the world) and these price pressures will likely be felt throughout a vast basket of consumer staples. For its own part, Ukraine is a significant (top 5) exporter of wheat, corn and sunflower oil to most of the world (particularly Africa and the Middle East) and disruptions to productive farmland from war is almost certain to cause food shortages (and price increases around the world).

While this is an economic newsletter and we therefore focus on economic effects, it should also be noted that the war in Ukraine occurs at an unimaginable cost in both lives lost and displacement of individuals from their homeland. Nothing we have said or will say is intended to diminish the gravity of the situation on the ground or the human suffering that is undoubtedly occurring in that part of the world.

A Note on Asia-Pacific: As noted in prior issues, China continues to experience a significant slow-down in economic activity (primarily driven by the implosion of its property sector and its “Zero-COVID policy” which locks down major economic centers for extended periods to limit the spread of COVID variants). China’s slow-down has the added effect of snarling supply chains around the world (since it is a source of many goods globally) and is likely to continue to add upward pressure on inflation from the supply side.

Triffin’s Paradox

As a result of the economic developments mentioned above, the global economy has entered a period where central bank interests are no longer aligned. Most notably, the domestic economic interests of the anglosphere (U.S., U.K., Canada and Australia) have diverged from the Eurozone and the emerging markets.

The anglosphere loosely speaking are exporters of capital and investment. With inflation raging domestically it is in the best interest of these nation’s to tighten policy restrictively to destroy demand (as noted above this appears to be the intent of the Federal Reserve, i.e. the central bank that controls the world’s reserve currency). The result of restrictive policy in the primary exporter of capital is less investment and higher costs of capital abroad (in the Eurozone and emerging market economies). This effect is most severe in nations that are also importers of food and energy, as these nations effectively become squeezed from both sides (their input costs increase at the same time as their capital and debt service costs increase).

This effect is already being felt in a number of nations, notably: (1) Sri Lanka has begun defaulting on its foreign debts and it is possible many other nations will follow suit (Sri Lanka debt default has begun; IMF Warns on Dangerous Global Debt Burden); (2) Russia has begun the process of default (although this is due to US Treasury sanctions and not specifically tightening policy); (3) China has made multiple attempts to prop up a slowing economy (by attempting to ease credit); and (4) Japan has made efforts to defend against rising bond yields (which has the corresponding effect of significantly devaluing the Japanese Yen).

As the anglosphere continues to act with the interests of its own domestic economies in mind, the side-effect of involuntarily tightening conditions abroad in economies where growth is already sputtering could very well have the effect of causing fissures throughout the global financial system.

Be On The Look-Out:

Inflation Expectations: As noted above, the primary driver of Federal Reserve policy is inflation and inflation has increasingly become entrenched. Be on the look-out for increases in inflation caused by conflict in Europe and/or supply chain bottlenecks in Asia.

Pace of Rate Increases: Changes in inflation expectations drives the pace of rate increases. The Fed is currently calling for ~7 hikes of between 25 and 75bps (with 50bps being the most likely pace). Be on the look-out for any accelerations (or de-accelerations) in the pace of hiking in response to any changes in inflation expectations.

Pace of Balance Sheet Run-off: While much has been made of the Federal Reserve’s intended hiking cycle, there is still a great deal of uncertainty surrounding the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet. Be on the look-out for expectations of the pace of the run-off (and any outright selling of securities) as this will significantly impact the long-end (and risk assets).

Recession: As former Governor Bill Dudley noted, the proposed policy of the Federal Reserve nearly ensures a recession. Be on the look out for slowing growth (and rising unemployment) that could tip the economy into recession.

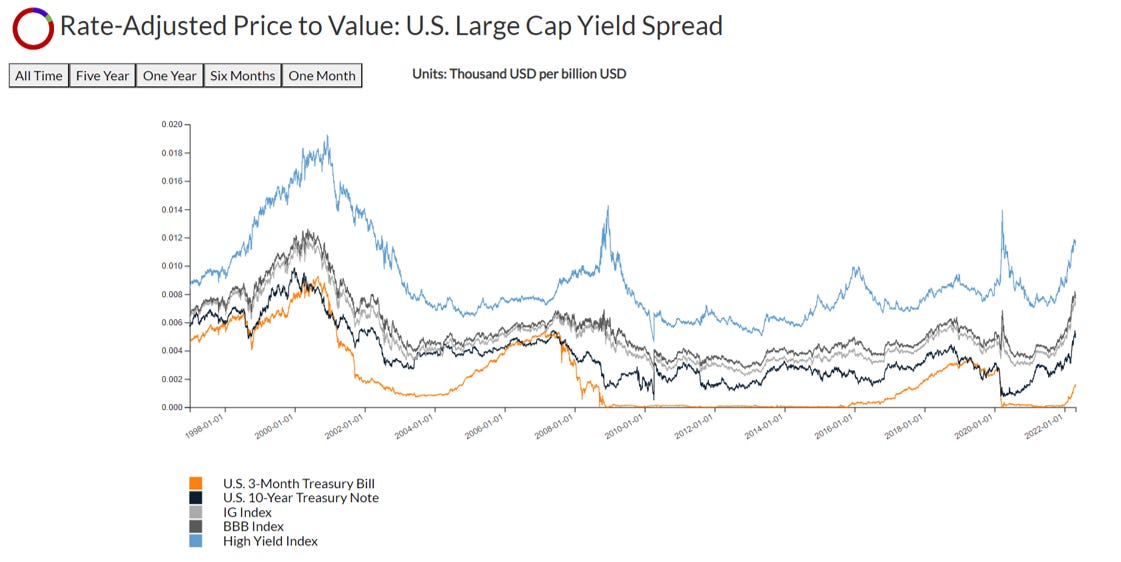

Corporate Credit Spreads, Housing Activity and Repo Markets: Raising rates into a slowing economy is almost certain to cause market distress. In particular, rate risk in the corporate bond market and MBS has the potential to bleed through to corporate and housing activity. Repo markets may also cause funding issues for certain non-banks. (Notably, mortgage rates have already accelerated higher, which has caused a significant slow-down month-to-month in housing activity as a result.) Be on the look-out for widening spreads in the corporate bond market, distress in MBS and any repo market failures to deliver.

Distress in Emerging Markets: As the Federal Reserve tightens monetary policy, all countries with large US dollar needs (nearly all of the world) tighten involuntarily as well. Many countries (particularly Japan and emerging markets) have begun loosening economic policy as their nations’ growth as sputtered. Be on the look-out for deleterious affects of Federal Reserve tightening in these nations (whose easing attempts are likely to fail and as a result whose currencies are likely to feel pressure in the FX markets).

Of these six items, pay particular attention to credit spreads and FX issues. Because credit has preferential seniority (higher priority of claims) in the capital structure, it tends to display signs of distress before other markets. A careful eye on credit and FX could provide warning signs for distress to come in other markets.

Economic Snapshot

GDP: Q1 $24,382.683 Real GDP growth slowed at a rate of -1.4%. While this is a sign the US economy is slowing, it should be noted that nominally the economy continued to grow (just not at a rate which outpaced inflationary pressures).

Price: Stock market averages continue to remain near all-time highs with the S&P500 closing at 4,183.96 on April 27, 2022. It is notable, however, that prices are off the peak and trending down.

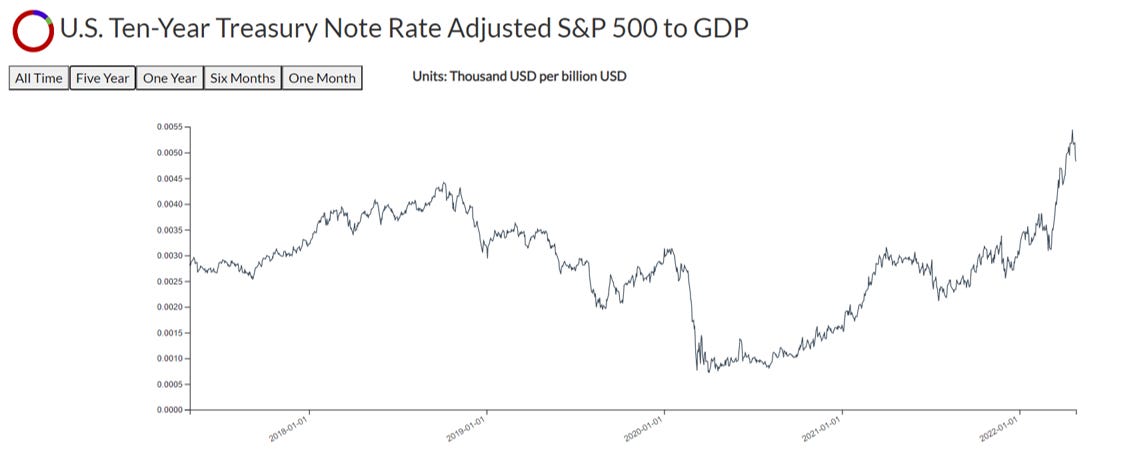

Price to GDP: Price to GDP ratios remain historically high with an S&P500 to GDP ratio of 0.1743 (down slightly from our January reading of 0.1847). This continues to exceed the Price to GDP ratios seen during the Dot-com bubble.

Interest Rates: The 10-Year Treasury Rate rose notably to 2.77 as of April 26, 2022 (up from 1.81 in January).

Rate-adjusted Price to GDP: Rate-adjusted price to GDP has risen notably over the last few months (owing largely to an increase in interest rates) and now sits above 2018 levels.

Yield Spreads: Corporate credit spreads have begun rising as interest rates have risen.

Yield-adjusted Price to GDP: Yield-adjusted Price to GDP has continued to rise (owing largely to increases in interest rates). Notably it is at levels last seen in 2020 (at which time the Fed stopped hiking and pivoted back to rate cuts). This is notable because the Fed is still only at the beginning of its current hiking cycle.

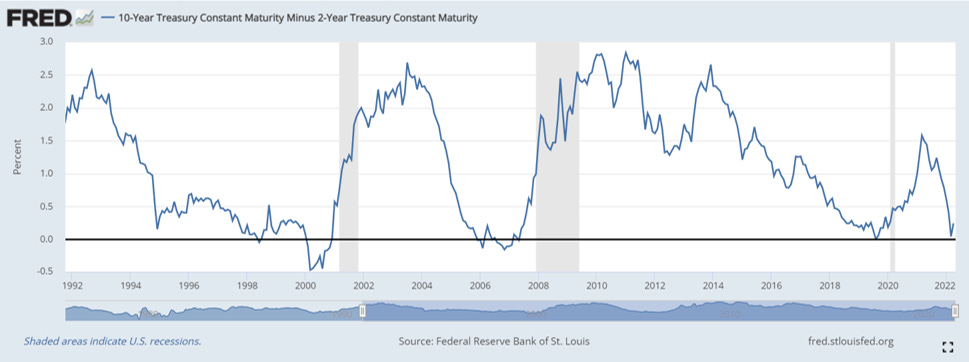

10-Year to 3-Month Treasury Spread: The 10-year to 3-month treasury spread has increased to 2.00 as of April 2022 (representing a mild steepening from the January reading).

Notably, this is a significant divergence from the 10-Year to 2-Year Treasury Spread, owing to a very large spread between 3-Month and 2-Year Treasuries. This is a historically rare event and represents a wide divide between the short-term market rate (2-Year) and the policy rate (3-Month).

Inflation Break-Evens: Intermediate and long-run inflation averages have ticked up notably and are hovering ~3% (well above the 2% long-run inflation target of the Federal Reserve).

Housing Affordability:

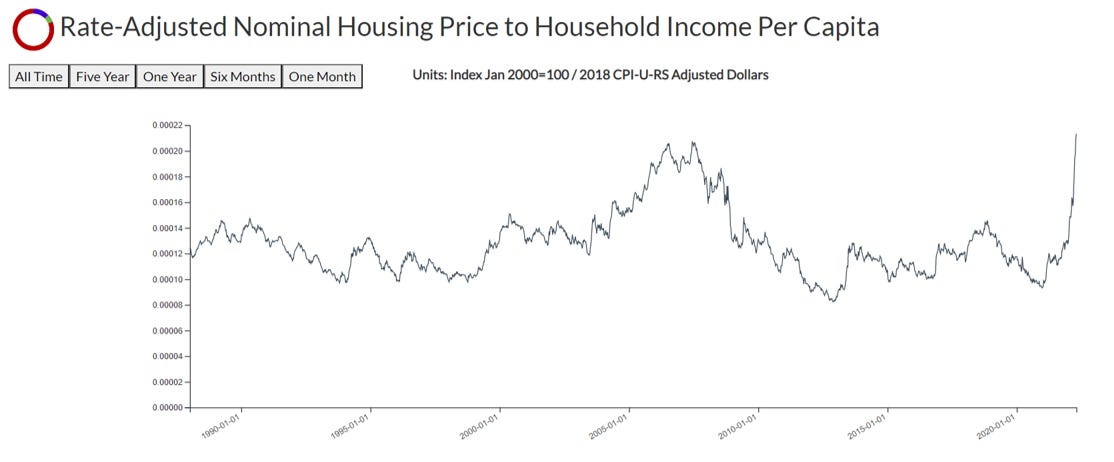

30-Year Mortgage-adjusted Housing Price to Household Income: Housing affordability has declined significantly since January as mortgage rates have skyrocketed. Notably, an estimate of average mortgage payments to average household income has reached circa 2006-2008 levels (i.e. levels last seen during the 2008 housing/financial crisis). The rate of change is also notable as it took only ~3 months for relative affordability to change from historic affordability to historic unaffordability.

Housing Price to Household Income: Housing affordability in absolute terms of housing price to household income exceeds levels last seen in the 2006-2008 housing/financial crisis.

Disclaimer

The data displayed in this report was developed by DeCotiis Analytics LLC (“DeCotiis Analytics”) using various public sources. DeCotiis Analytics is NOT a registered investment adviser and does not guarantee the accuracy or completeness of the information contained herein, or any data or methodology either included herein or upon which it is based. Individual investment decisions are best made with the help of a professional investment adviser.

Although effort has been taken to provide reliable, useful information in this report, DeCotiis Analytics does not guarantee that the information is accurate, current or suitable for any particular purpose. Data contained in this report are those of DeCotiis Analytics currently and are subject to change without notice. DeCotiis Analytics makes no guarantee or warranty of the accuracy of source data or the results of compilation of such data.

The information provided herein is for informational and educational purposes only. It should not be considered financial advice. You should consult with a financial professional or other qualified professional to determine what may be best for your individual needs. DeCotiis Analytics does not make any guarantee or other promise that any results may be obtained from using the content herein. No one should make any investment decision without first consulting his or her own financial advisor and conducting his or her own research and due diligence. To the maximum extent permitted by law, DeCotiis Analytics disclaims any and all liability in the event any information, commentary, analysis, opinions, advice and/or recommendations prove to be inaccurate, incomplete, unreliable or result in any investment or other losses. Content contained or made available herein is not intended to and does not constitute investment advice and your use of the information or materials contained is at your own risk.

Information from this report may be used with proper attribution. All original text, graphs and compilations of data contained in this document are copyrighted material attributed to DeCotiis Analytics. Any reproduction or other unauthorized use of material herein is strictly prohibited without the express written permission of DeCotiis Analytics.

an excellent summary! Thank you