Federal Reserve Tapering Implications (July 29, 2021)

Congress stalls on additional stimulus. Unemployment rate stalls. The Federal Reserve redefines “transitory” inflation to mean “permanent price increases”. The Federal Reserve begin

Economic Developments

A Stalled Congress: Since our last issue (May 2021), Congress has accomplished largely nothing on the economic front. Despite a great deal of discussion around a massive infrastructure package stemming back to the Presidential election, little progress has been made on passing a bill and any proposed fiscal stimulus seems likely to be severely stripped down from the massive spending initially proposed.

Inflation: Despite assurances from the Federal Reserve that inflationary pressures were due to primarily transient factors (mainly supply chain bottlenecks resulting from the COVID crisis), CPI has spiked up to ~5% by the time of this writing.

In a somewhat rambling explanation, the Federal Reserve Chairman at his most recent press conference sought to clarify the Federal Reserve’s stance on the meaning of “transitory” inflation to include “permanent price increases”, stating:

“The concept of transitory is really this. It is that the increases will happen. We’re not saying they will reverse. That’s not what transitory means. It means that the increases in prices will happen, so there will be inflation, but that process of inflation will stop so that there won’t be…when we think of inflation, we really think of inflation going up year, upon year, upon year, upon year. That’s inflation. When you have inflation for 12 months or whatever it might be…then you have a price increase but you don’t have an inflation process…Again, we don’t mean, I don’t mean, that producers are going to take those price increases back. That’s not the idea. It’s just that they won’t go on indefinitely…”

While the Fed Chair’s effort to walk back a prior more aggressive “transitory” position using a definition of “transitory” that includes permanent price increases is somewhat laughable, the larger point is likely correct as noted by the Chairman. Mainly absent additional fiscal stimulus from Congress (currently stalled as noted above) forcing additional dollars into the hands of the consumer, the rate of price increases is likely to decline as supply chain disruptions moderate.

Unemployment: The unemployment rate has fallen to 5.9%, but is still significantly above the sub-4% rate of unemployment enjoyed pre-pandemic. Additionally and as the Federal Reserve Chairman noted, the stated unemployment figure “understates the short fall in employment, particularly as participation in the labor market has not moved up…for most of the past year.”

Federal Reserve Asset Purchases: Given a choice between the dual mandate of price stability and maximum employment, the Federal Reserve has opted to error toward the side of maximum employment, primarily by maintaining a zero interest rate policy and by purchasing assets which facilitate a steady flow of credit to businesses and individuals. While maintaining this ultra-loose monetary policy stance, the Fed has largely ignored inflationary effects, choosing to regard them as “transitory” (including, evidently, to the extent such inflation results in “permanent price increases”).

However, by suppressing price discovery in the credit markets (i.e. interest rates) by purchasing assets for which there is less actual demand, the Federal Reserve has also succeeded in exacerbating a third problem (that is absent from it’s mandate, but often implicit in policy decisions), mainly, inflating asset bubbles across capital markets. This is most notable in credit markets (where interest rates are at historic lows for the riskiest credits and issuance of new debt continues at record highs) but also affects more sympathetic assets like housing, where Federal Reserve purchases of mortgage-bonds at a rate of at least $40 billion a month have driven mortgage rates to historic lows and correspondingly, housing prices to historic highs (US Housing Prices grew ~12% year over year in June 2021; the year over year average growth rate from 1992 to 2021 is ~5.3%).

A Rock and a Hard Place: Regardless of the definition of “transitory” employed, it is clear that inflation has been more substantial than the Federal Reserve expected and the unemployment rate has become somewhat stuck effectively trapping the Federal Reserve between it’s dual mandate of price stability and maximum employment.

While price stability can be somewhat ignored until a persistently high rate of inflation occurs (the Federal Reserve drawing this line at a 2% average inflation target), failing to act to combat inflation increasingly comes into focus as a reflection on the Federal Reserve’s credibility. Similarly, market participants begin to doubt the ability of the Federal Reserve to deploy it’s customary “tools” (mainly interest rate increases) without destroying the global debt markets.

Given, the unholy trifecta of asset price bubbles fueled by Federal Reserve asset purchases, inflation driven by fiscal stimulus and persistently high unemployment, the Federal Reserve’s levers for controlling the economy become more tenuous. That is to say, the Federal Reserve is left with a Hobson’s Choice, between (1) raising rates and/or tapering asset purchases, preventing inflation, but destroying the credit markets (particularly corporate credit and housing), damaging the co-dependent equity markets (stocks, housing prices, etc.) and increasing unemployment (as business fail or cut-back on workers); or (2) maintaining rates and/or asset purchases, protecting capital markets from default and keeping workers employed, but eroding the purchasing power of the US dollar.

For his part, the Federal Reserve Chairman at his June 17th press conference, signaled that given the choice between persistently high inflation and maximum employment, price stability would likely win the day.

“If we see inflation expectations or inflation moving up in a way that is really materially above what we would see as consistent with our goals and persistently so, we wouldn’t hesitate to use our tools to address that. Price stability is half of our mandate and we would certainly do that.”

Tapering: Given the Federal Reserve’s implicit need to maintain it’s credibility together with signaling from Federal Reserve members, many market participants have begun to expect the Fed to begin tapering asset purchases in the near future (over the next 2 to 4 months). Given the Federal Reserve’s oversized role in the debt markets, a tapering of purchases by the Federal Reserve serves as a de facto “tightening of financial conditions” (the absence of expected demand causing dynamic pricing changes) and is likely to cause significant upheaval in credit markets.

Standing Repo Facility and Reverse Repo Facilities: Presumably anticipating this, the Federal Reserve has stood up two new Standing Repo Facilities (one for the domestic and one for international markets). While maintaining a Reverse Repo Facility, which is currently in use.

Globally, the US dollar and US treasury notes provide “liquidity” for most financial institutions. That is to say, most financial institutions find themselves in a situation where they need to rapidly acquire US dollars or rapidly dispose of US dollars to meet various financing needs.

During times of “tightening”, US dollar demand typically increases (culminating in what amounts to a “run” on US dollars when debt crises ensue or as it’s also referred “liquidity crises” arise as financial institutions become unable to convert assets into currency with which they can transact). During times of “loose” policy, US dollar demand typically decreases (since the system is being flooded with US dollars by the Federal Reserve) which culminates in a “run” on high quality collateral (typically US treasury notes of some duration). Collectively, this supply and demand balancing occurs in the “money markets”, most typically, through “repurchase agreements” among financial institutions and the US Treasury markets.

Given the ultimate need for US dollars in a crisis, regardless of industry, most debt crisis back up into the repo or money markets, as a dollar shortage causes a “liquidity crisis” among financial institutions. Financial institution resiliency falls under the purview of the Federal Reserve and has been a specific focus of the Federal Reserve (particularly following the Global Financial Crisis and the passage of Dodd-Frank).

Given this focus, the Federal Reserve appears to be front-running potential liquidity and collateral issues by standing up facilities by which US dollars can be rapidly added or removed from the money markets as required. In effect, the money markets are being federalized by the Federal Reserve, such that as a standing policy, the Federal Reserve can prevent a liquidity crisis by adding US dollars to both foreign and domestic financial institutions to prevent a run (via the Standing Repo Facility) or prevent a collateral crisis by removing US dollars from both foreign and domestic financial institutions (via the Reverse Repo Facility). The Reverse Repo Facility also provides some degree of a floor under Treasury rates, as demand for Treasury notes (which would drive rates lower) can be effectively diverted into the Reverse Repo Facility.

From a structural perspective, this represents a somewhat radical overall of money markets and Treasury markets by putting money markets and lending rates firmly within the control of the Federal Reserve (i.e. the standing repo facilities together with the reverse repo facility and the transition to SOFR–a market rate based on collateralized transactions in the US Treasury Overnight Repo market–from LIBOR–a stated inter-bank lending rate–represent a government institutionalization of money markets and lending rates).

From a policy perspective, it signals tapering is likely in the near term, given the Federal Reserve is anticipating and removing the primary crisis mechanism by which bailouts are needed during times of credit distress. Or said another way, by removing liquidity issues from the marketplace, the solvency issues of creditors are free to be left to their own machinations while the Federal Reserve tightens financial conditions.

Fundamental Analysis

GDP: Q2 $22,722.581 GDP has increased steadily since the shock of the pandemic (owing in part) to fiscal stimulus packages which have put money directly into the hands of consumers. Notably Q2 GDP grew at a slower rate than anticipated (likely owing to a lack of continued fiscal support).

Price: Stock market averages continue to remain at or near all-time highs with the S&P500 closing at 4,419.45 on July 29, 2021.

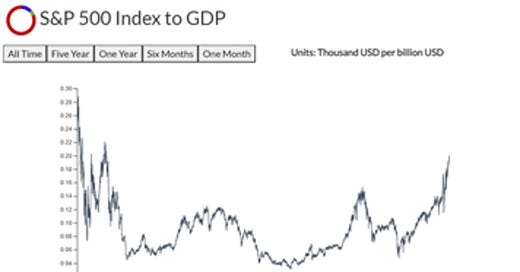

Price to GDP: Price to GDP ratios remain historically high with an S&P500 to GDP ratio of 0.192. This exceeds the Price to GDP ratios seen during the Dot-com bubble.

Interest Rates: The 10-Year Treasury Rate fell notably to 1.26.

Rate-adjusted Price to GDP: Rate-adjusted price to GDP has fallen somewhat (owing largely to a decline in interest rates), but remains elevated.

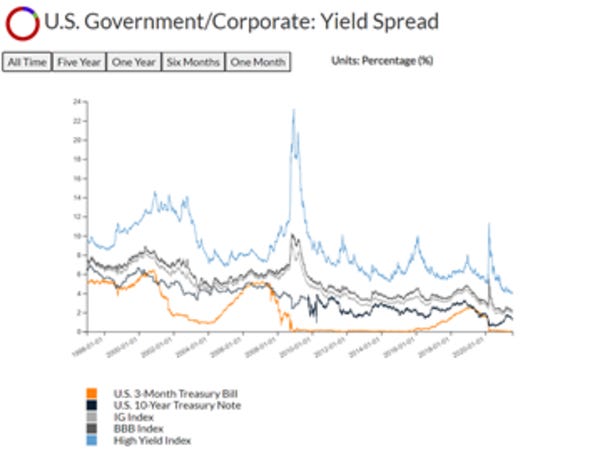

Yield Spreads: Corporate credit spreads continue to remain at historic lows.

Yield-adjusted Price to GDP: Yield-adjusted Price to GDP has continued to rise moderately.

10-Year to 3-Month Treasury Spread: The 10-year to 3-month treasury spread has declined to 1.22.

Disclaimer

The data displayed in this report was developed by DeCotiis Analytics LLC (“DeCotiis Analytics”) using various public sources. DeCotiis Analytics is NOT a registered investment adviser and does not guarantee the accuracy or completeness of the information contained herein, or any data or methodology either included herein or upon which it is based. Individual investment decisions are best made with the help of a professional investment adviser.

Although effort has been taken to provide reliable, useful information in this report, DeCotiis Analytics does not guarantee that the information is accurate, current or suitable for any particular purpose. Data contained in this report are those of DeCotiis Analytics currently and are subject to change without notice. DeCotiis Analytics makes no guarantee or warranty of the accuracy of source data or the results of compilation of such data.

The information provided herein is for informational and educational purposes only. It should not be considered financial advice. You should consult with a financial professional or other qualified professional to determine what may be best for your individual needs. DeCotiis Analytics does not make any guarantee or other promise that any results may be obtained from using the content herein. No one should make any investment decision without first consulting his or her own financial advisor and conducting his or her own research and due diligence. To the maximum extent permitted by law, DeCotiis Analytics disclaims any and all liability in the event any information, commentary, analysis, opinions, advice and/or recommendations prove to be inaccurate, incomplete, unreliable or result in any investment or other losses. Content contained or made available herein is not intended to and does not constitute investment advice and your use of the information or materials contained is at your own risk.

Information from this report may be used with proper attribution. All original text, graphs and compilations of data contained in this document are copyrighted material attributed to DeCotiis Analytics. Any reproduction or other unauthorized use of material herein is strictly prohibited without the express written permission of DeCotiis Analytics.