Carefully Fall Into the Cliff

Central Bankers prepare for a fight with inflation while growth slows around the world

Economic Developments

The Beginning of the End (Part Deux):

In our last issue (The Beginning of the End - October 28, 2021), we noted that the Federal Reserve’s bias toward inaction had increasingly come under strain as inflation accelerated and growth deteriorated around the globe. Specifically, we noted that:

1) failing to combat inflation increasingly comes into focus as a reflection on the Federal Reserve’s credibility;

2) delays in combating inflation necessitate larger, more dramatic efforts (mainly rate hikes) to be effective;

3) growth around the world was slowing, leaving the Federal Reserve in a position where it may need to tighten financial conditions (or at a minimum be unable to further loosen policy), while growth falters; and

4) to be on the look-out for credit conditions deteriorating abroad.

As the months have progressed, we have seen these 4 observations unfold in real-time.

First, in a message delivered in front of Congress on November 30, 2021, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell decided to retire the word “transitory”, stating “I think it’s probably a good time to retire that [transitory] word” (separately, he also called inflation “frustrating” in prior remarks). This change in messaging represented a tacit admission that the Federal Reserve’s credibility was/is suffering from disconnected public messaging in the face of persistent inflation. (Fed Chairman Jerome Powell retires the word 'transitory' in describing inflation)

It is notable that leading up to this change in messaging, leading economists began to increasingly pressure the Fed in a series of public statements; contradicting Fed policy, directly attacking Fed credibility and/or highlighting the risk of a “policy error”. (Fed Losing Credibility Over “Transitory” Inflation Talk: Mohammed El-Erian; Larry Summers Urges Fed to Signal Four '22 Rate Hikes to Regain Credibility)

Second, at its December 15, 2021 meeting, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell announced the decision to double the speed of tapering Federal Reserve bond purchases, thereby moving the effective end of Quantitative Easing (“QE”) from July to March. Specifically the Chair noted, “Markets are going to be sensitive to it, and we thought this was doubling the speed. We are basically two meetings away now from finishing the taper. We thought that was the appropriate way to go.” (A Full Recap of the Fed Decision with Powell highlights and instant investor insight)

Third, on January 26th, the Federal Reserve indicated the intention to raise the Federal Funds rate (the benchmark rate) at it’s March meeting (signaling the beginning of an active tightening cycle) and noted a Federal Reserve Balance Sheet run-off could follow rate hikes (a process by which bonds currently held from prior purchasing/QE programs are allowed to mature without the proceeds being reinvested in further purchases, thus decreasing the total assets held by the Federal Reserve). If a faster tightening cycle is warranted, the Balance Sheet run-off could also take the form of active selling (although most likely this would be coordinated with the US Treasury, such that US Treasury debt would be issued and the proceeds of such issuance would be used to purchase bonds held on the Federal Reserve Balance Sheet, thereby reducing the Federal Reserve’s Balance Sheet with minimal disruption to capital markets).

In sum, in just three short months, the forecasted speed and magnitude of tightening financial conditions increased rapidly (far quicker than previously articulated) as Federal Reserve messaging changed from (1) inflation is transitory to (2) inflation is not transitory to (3) Quantitative Easing will end to (4) Quantitative Easing will end and rate hikes will be implemented to (5) Quantitative Easing will end, rate hikes will be implemented and Quantitative Tightening may be instituted.

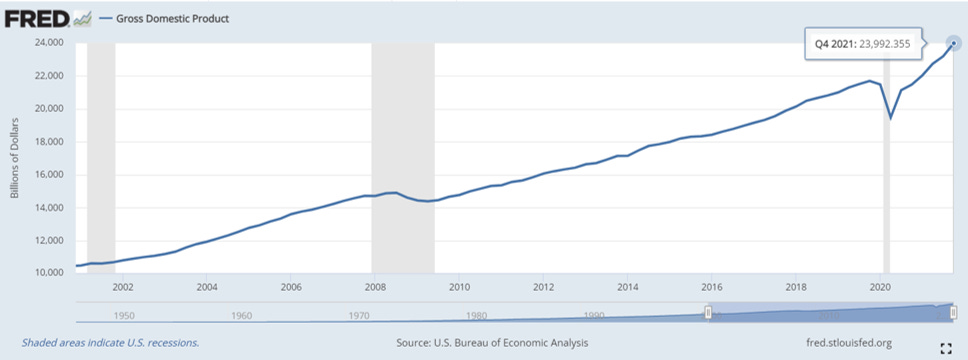

Fourth, Q4 GDP gains measured at 6.9% (up markedly from Q3’s 2.3%) to close out annualized GDP for 2021 at 5.5%. It is notable, however, that of this 6.9%, ~4.9% came from inventory increases, which more likely reflects an effort to stock-pile inventory ahead of rising inflation amid supply shortages than real economic growth (GDP grew at a 6.9% pace to close out 2021, stronger than expected despite omicron spread). It is also notable that annualized GDP for 2021 of 5.5% represents below trend economic growth as compared to pre-COVID trend and forward looking indicators (specifically, a rapid decline in consumer confidence) suggest additional slowing in future quarters (likely due in part to rising costs from inflation).

Despite expected slowing, the Federal Reserve remains committed to it’s tightening cycle (noted above) and will most likely be tightening financial conditions into a significant slow-down (perhaps even a recession) . The US political apparatus also appears committed to this plan as the Federal Reserve has received support from the White House (in public messaging) to begin tightening financial conditions to combat inflation (Biden backs Federal Reserve Tightening Plans).

Fifth, credit conditions have begun to deteriorate abroad. Most notably, China’s property sector has begun to slowly implode. Chinese Real Estate giant Evergrande, formally defaulted earlier in the month of December and as of January is under consideration for being broken up in a restructuring. Similarly, other developers have or are expected to default as of this writing (Delinquent Shimao, Kaisa units named and shamed as defaults rise). This is notable because (1) the real estate sector is the single biggest component of the China’s economy at ~28% of GDP in 2021, (2) slowdowns in the Chinese property sector have a spillover effect into other areas of Chinese manufacturing, and (3) the Chinese real estate sector has an unknown but significant amount of onshore and off-shore debt (China’s property distress sours steel sector in warning sign for economy).

Slowing of the Chinese real estate sector has serious implications for the global economy for three primary reasons: (1) as the second largest economy in the world a slowdown in Chinese growth has the effect of slowing growth globally; (2) slowing manufacturing in China significantly affects supply chains in the West which tends to result in persistent supply-side cost-push inflation in the West (disruptions are further exacerbated by China’s “zero-COVID” policy which periodically shuts down areas, frequently manufacturing cities, to contain COVID-outbreaks); and (3) liquidation proceedings of real estate in China are likely to favor on-shore debt holders over off-shore debtors, which would effectively transfer credit losses from China to the rest of the world (primarily Western Europe and North America), while Chinese creditors are made whole (or, at least, are less significantly impacted).

Carefully Fall Into the Cliff:

Given the foregoing, a soft-landing of the global economy seems increasingly unlikely. To take stock, we have to consider the position ~12 years of Quantitative Easing has left the markets. At this point in history we are simultaneously staring over the edge of: (1) a historic asset bubble, (2) historic aggregate debt levels, (3) inflation, (4) the end of the loosest monetary policy in history, and (5) slowing economic activity. How carefully can one expect global markets to fall into this cliff? How carefully can the Federal Reserve drain liquidity from the global financial system without causing the financial system to collapse?

To reset the scales and return from the distortion ~12 years of Federal Reserve policy has caused, the Federal Reserve is left with a Hobson’s choice between 1) high prices, 2) high debt, 3) inflation, 4) growth and 5) employment. Notably of these 5 items, only (3) inflation and (5) employment are expressly within the mandate of the Federal Reserve (although growth is implicitly included since growth directly impacts employment and debt is implicitly included because the primary way the Federal Reserve combats inflation is by controlling the base interest rate and therefore the flow of credit).

Faced with this choice, the Federal Reserve is most likely to (and is signaling it will) chose to combat inflation by raising interest rates and “shrinking” (or at least failing to add to) its balance sheet.

Raising interest rates has the effect of increasing the cost of credit (i.e. the price of borrowing money). Raising the cost of credit slows inflation (because credit is a form of money, there is therefore less money in circulation), but it also slows growth (since debt growth increases purchasing power/balance sheet leverage) and makes current debt harder to service (i.e. it becomes difficult to refinance or roll maturing debts forward at a similar cost, take on new debt and/or to pay existing debts). Slowing growth and increasing the cost of debt service squeezes profit margins which has a deleterious affect on expected future profit, expected growth multiples and therefore prices. When businesses are unable to increase profits they often respond by cutting costs (or otherwise shrinking), which frequently leads to layoffs (since employees are typically one of the most expensive aspects of running an enterprise).

A “shrinking” Federal Reserve balance sheet has a similar effect. That is to say, Federal Reserve purchases provide demand for issuance of debt securities (mainly bonds, i.e. Treasury notes and agency-MBS). Without these Federal Reserve purchases, demand decreases which leaves a surplus of securities in the market. As a result of a surplus in bonds, prices of these securities fall (and the cost of borrowing rises, i.e. yields rise in an effort to attract purchasers). This process is exacerbated if the Federal Reserve “shrinks” it’s balance sheet through outright sales (as the Federal Reserve would be adding additional notes for sale into a market with a surplus of securities already).

The sum of these two actions combats inflation, but also reduces the available supply of money being provided by the Federal Reserve (i.e. Quantitative Tightening). Tightening financial conditions in this way forces debt markets (and therefore equity markets financed by debt markets) to reprice.

The current distortion in prices (from a “true” price or price without Federal Reserve support) is so great that many market participants have come to conclude the Federal Reserve simply cannot allow it to happen because doing so would destroy the bond market (and other dependent markets and therefore the financial system). It is our opinion that this view is incorrect.

While it is true, price discovery is horrendously distorted, it does not necessarily follow that the Federal Reserve will not drive the financial system directly off of the cliff.

As background, in addition to its dual mandate of price stability (inflation) and maximum employment, the Federal Reserve is also responsible for the “financial plumbing” of the US financial system (and by extension the global financial system because the US is the reserve currency of the world). That is to say, the Federal Reserve is responsible for the proper function of US dollar markets (domestically and internationally) and Treasury markets (Treasuries being a form of long duration USD in a manner of speaking that are used across balance sheets around the world and therefore need to be able to be converted quickly into cash either by being posted as collateral or sold outright).

Since the early 2000s, when financial crises occurred (typically at the end of the business cycle as defaults or deleveraging occurred), the rush to cash that arose inevitably caused distress in US dollar (as the reserve currency) and US Treasury markets. When this distress occurred, the Federal Reserve stepped in and provided “funding” to these markets (i.e. the Federal Reserve made outright purchases in order to prevent a run on cash and to provide cash to the market to prevent a “run”) as consistent with its mandate of providing “smooth market function” of the “plumbing” of the financial system. As a second order effect this also buoyed other (riskier) forms of credit and risk assets (support to which which investors/traders have become accustomed in their positioning).

As noted in our July 31, 2021 report (Structural Changes in Treasury Markets Suggest Policy Shift), the Federal Reserve has been slowing working on a solution to solve this “forced” funding or subsidizing of markets through the use of financing facilities, mainly a Standing Repo Facility (SRF) and Reverse Repo Facility (RRP). In short, the Federal Reserve believes it has solved for the US dollar and US treasury “run” on institutions (by effectively nationalizing the US dollar and US Treasury markets into a state-controlled market). As a result, there should be no need to “fund” another crisis in risk assets (since even though a dash for cash is likely to occur, cash can be freely provided at a financing rate that adequately controls the flow of dollars to and from the marketplace). Or said another way, the metaphorical broken leg has been fixed, the cast can come off and the morphine drip can end (after ~12 long years or longer depending on how you count).

Given the forgoing, it’s reasonable to assume the Fed intends to allow asset prices to collapse (since collapsing asset prices shouldn’t “break” the financial system’s plumbing). There is obviously a limit to how far the Federal Reserve can allow markets to fail (i.e. at some point asset prices collapsing adversely affects employment to such a degree that the Federal Reserve’s employment mandate takes center-stage again). However, this limit is likely much lower than market participants, who have become accustomed to the Federal Reserve subsidizing any signs of distress, believe (particularly in the face of inflation, which causes the Federal Reserve to balance societal interest in employment distress against the potential damage of entrenched inflation).

Be On The Look-Out:

Given the forgoing, it is important to stay vigilant as the Federal Reserve peers over the edge of the cliff. It is also important not to place undue reliance on the Federal Reserve and its past fervor to bail-out market participants from poor risk positioning. For all intents and purposes, the Fed “put” is dead (or at a minimum greatly diminished).

Be on the look-out for:

Rapid deterioration in credit conditions (whether caused actively by the Federal Reserve via tightening financial conditions or stalling growth). Deterioration in credit markets, particularly from abroad, could spill over into global markets. It is also important not to expect the Federal Reserve to deploy a parachute immediately in the face of distress as it may (intentionally or unintentionally) permit the financial system to fall over the cliff until true price discovery (and deleveraging of excess) has occurred.

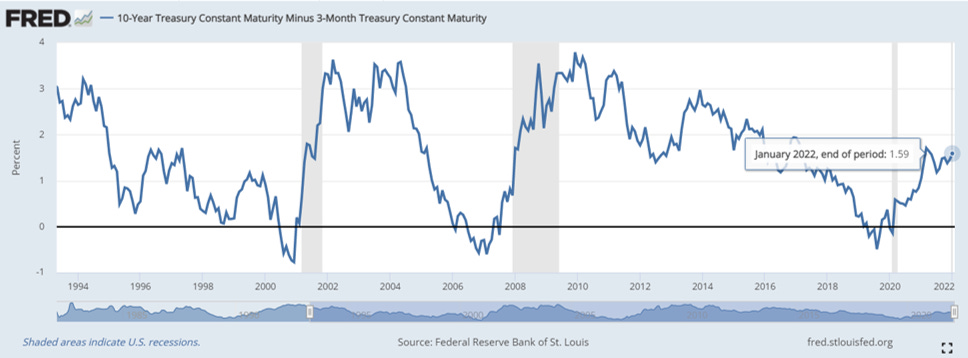

Rising mortgage rates and corporate delinquencies. As mortgages rates rise, housing demand and housing prices could be significantly impacted (a rise to as little as 4% in 30 year mortgages could spell trouble for housing markets). Similarly, as corporate rates rise be on the look-out for delinquencies (a 10-year treasury rate of as little as ~2% could cause spell trouble across bond markets).

Distress in emerging markets. Because the US dollar is the reserve currency of the world and most debt (i.e. foreign debt) is denominated in US dollars, as the Federal Reserve tightens financial conditions domestically, it also tightens financial conditions abroad. This may result in tightening of financial conditions in countries whose economies are already sputtering and/or in need of looser financial conditions. Similarly, as delinquencies rise and demand for dollars increase (to pay off US-denominated debt), dollar strength can cause a spiral of stress on emerging economies (and their governments) as increased dollar strength makes it increasingly more difficult to pay debts.

As a final note, it is important to recognize that markets are non-linear systems. As financial conditions transition between paradigms (from a deflationary decreasing interest rate environment to an inflationary increasing rate environment), volatility typically erupts as market participants struggle to understand their new environment (i.e. some folks remain anchored in the past, some misprice the future, etc.). During such a period, significant price swings can occur. Even though (as noted above) true price discovery (if permitted by the Fed) seems to support lower asset prices, the path to such resolution is unlikely to be linear and will probably be marked with large violent swings. It is a treacherous economic environment and should be approached with caution.

Carefully fall into the cliff.

Economic Snapshot

GDP: Q3 $23,992.355 GDP growth increased at a rate of 6.9% owing in part to a build up of inventories amid inflationary pressures and supply chain disruptions.

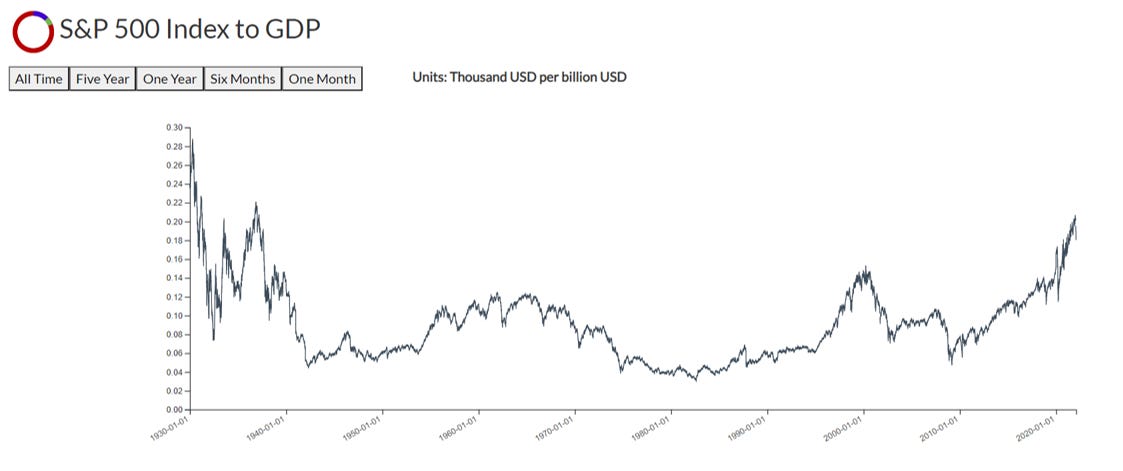

Price: Stock market averages continue to remain near all-time highs with the S&P500 closing at 4,431.85 on January 28, 2022.

Price to GDP: Price to GDP ratios remain historically high with an S&P500 to GDP ratio of 0.1847. This exceeds the Price to GDP ratios seen during the Dot-com bubble.

Interest Rates: The 10-Year Treasury Rate rose notably to 1.81 as of January 27, 2022.

Rate-adjusted Price to GDP: Rate-adjusted price to GDP has risen notably over the last few months (owing largely to an increase in interest rates and market prices).

Yield Spreads: Corporate credit spreads continue to remain at historic lows (although they have ticked up slightly over the last few months).

Yield-adjusted Price to GDP: Yield-adjusted Price to GDP has continued to rise moderately (owing largely to increases in asset prices and interest rates). Notably it has reached a level last seen in 2018 (during the Fed’s last attempt at a rate hiking cycle).

10-Year to 3-Month Treasury Spread: The 10-year to 3-month treasury spread has increased to 1.59 as of January 2022.

Disclaimer

The data displayed in this report was developed by DeCotiis Analytics LLC (“DeCotiis Analytics”) using various public sources. DeCotiis Analytics is NOT a registered investment adviser and does not guarantee the accuracy or completeness of the information contained herein, or any data or methodology either included herein or upon which it is based. Individual investment decisions are best made with the help of a professional investment adviser.

Although effort has been taken to provide reliable, useful information in this report, DeCotiis Analytics does not guarantee that the information is accurate, current or suitable for any particular purpose. Data contained in this report are those of DeCotiis Analytics currently and are subject to change without notice. DeCotiis Analytics makes no guarantee or warranty of the accuracy of source data or the results of compilation of such data.

The information provided herein is for informational and educational purposes only. It should not be considered financial advice. You should consult with a financial professional or other qualified professional to determine what may be best for your individual needs. DeCotiis Analytics does not make any guarantee or other promise that any results may be obtained from using the content herein. No one should make any investment decision without first consulting his or her own financial advisor and conducting his or her own research and due diligence. To the maximum extent permitted by law, DeCotiis Analytics disclaims any and all liability in the event any information, commentary, analysis, opinions, advice and/or recommendations prove to be inaccurate, incomplete, unreliable or result in any investment or other losses. Content contained or made available herein is not intended to and does not constitute investment advice and your use of the information or materials contained is at your own risk.

Information from this report may be used with proper attribution. All original text, graphs and compilations of data contained in this document are copyrighted material attributed to DeCotiis Analytics. Any reproduction or other unauthorized use of material herein is strictly prohibited without the express written permission of DeCotiis Analytics.